Experiences of imprisonment

Physical constriction and malnutrition

The SS housed more than 6,300 Jews in the 18 barracks of the »small camp« in November 1938. There were no beds. The prisoners had to sleep in their clothesa on straw laid out on the floor.

The food provided to the men was insufficient, both in terms of quality and quantity. In respect of the physically demanding work they received too little fat in their diet. There was a soup in the morning, army bread with a spread on top for the mid-day meal, and some sort of stew in the evenings. The situation improved with the opportunities to purchase items in the »camp canteen,« which offered food and tobacco at exorbitant prices.

Reduced to a number

During the concentration camp admission process, every man received a number that replaced his name. The SS sought to completely de-individualize their victims with such measures, including the prison uniforms and the shaving of their heads.

The men – robbed of their individuality and reduced to a number – became part of an anonymous mass. Many Jewish men saw this transformation as the worst experience of their imprisonment. Gerhard Nassau later described Sachsenhausen concentration camp as a »country of numbers where the time stands still and the men have no names.«

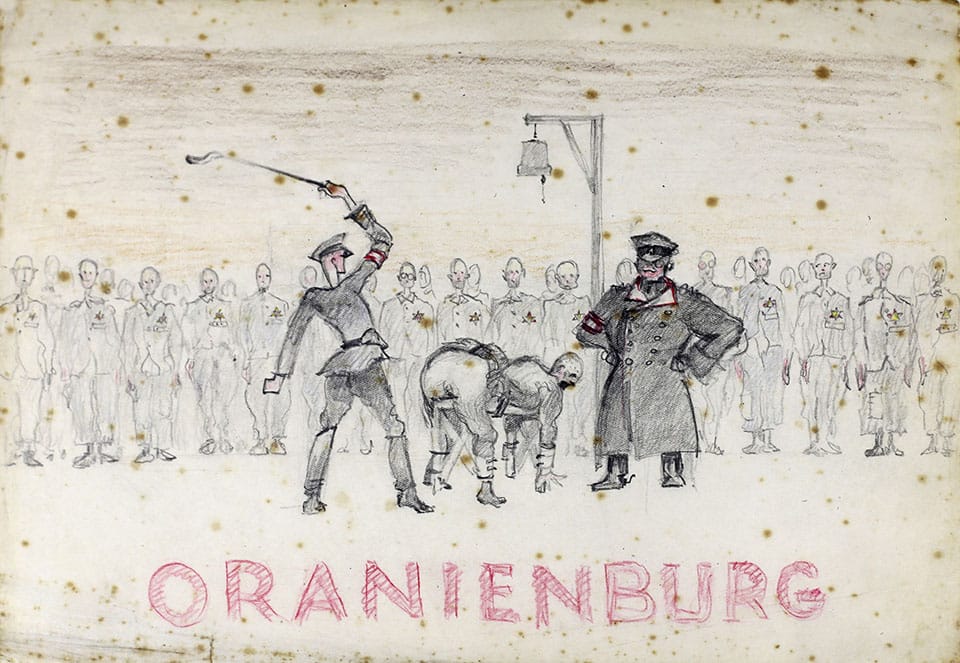

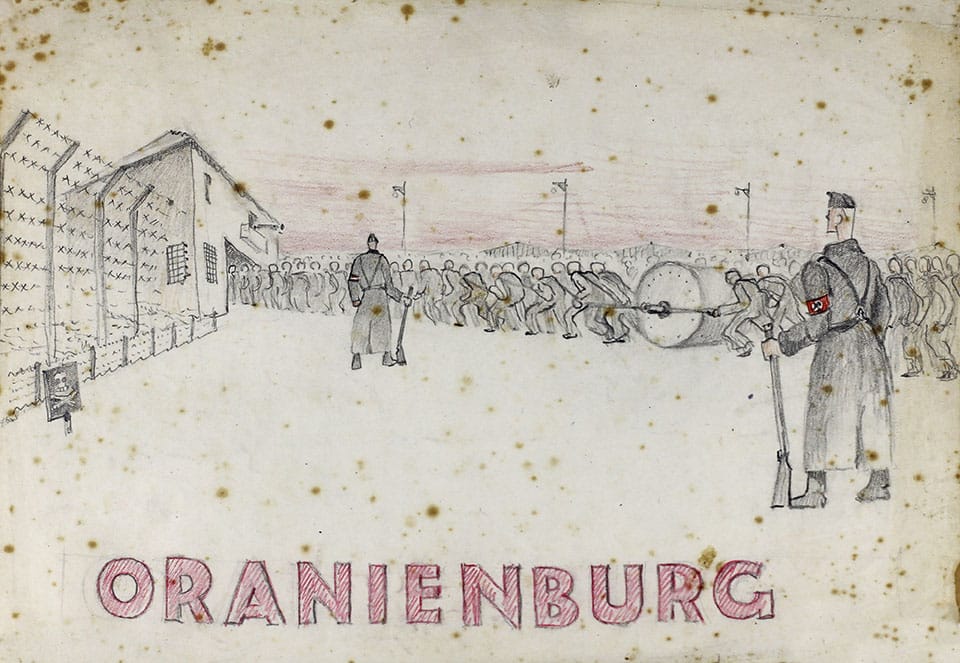

Protracted torments: The roll call

Another profound camp experience was the roll call parades that were held twice a day. As the Jewish prisoner Erich Kohlhagen later wrote, »the counting of the prisoners was one of the most important matters in the concentration camp.« People were allowed to die, »but woe be upon us if someone was missing.« Even sick and utterly weakened prisoners had to stand for roll call for hours, in cold and wet conditions. This frequently resulted in frostbite and the amputation of extremities. Fear of the SS and their kicks and blows was pervasive. The weakest often became the victims of sadistic torments.

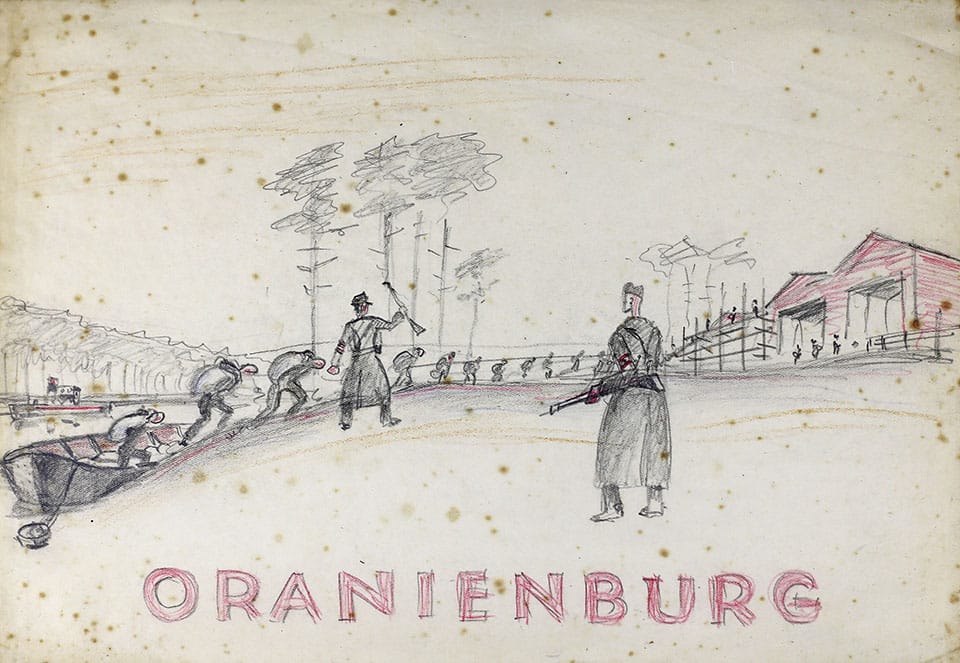

Heavy, tiring physical labor

Jewish prisoners were forced above all to drill and exercise in the days following their arrival. Later, the SS forced the men to perform exhausting and often meaningless work, primarily to humiliate them. They had to move piles of sand from one place to another, or clear snow with their bare hands, which resulted in frostbite. Others had to work in the dreaded external work detail at the brickworks, where they had to haul sand and heavy sacks of cement. Because the camp was overfilled, however, the SS were not able to give all of the prisoners a job. Whoever wasn’t assigned to a work detail had to perform work in the barracks or exercise.

Intimidation through arbitrary SS terror

Along with constant worries about the future, the despotism of the SS caused the most torment. The camp commandant told the Jewish men upon their arrival that they had to follow the camp’s rules. Yet the SS intentionally left the prisoners in the dark about the actual rules and the penalties for breaking them. This made the men, as one of them later wrote, »vulnerable people subjected to the whims of our tormentors;« the prisoners were exposed and helpless before the fear of being punished.The Jewish men also experienced the imposition of punishments on other prisoners, which they were forced to watch or listen to, as terrorizing.

Degradation and humiliation

The ignominious conditions of the arrest and the camp made their imprisonment in the concentration camp an existential catastrophe. Along with the physical injuries suffered in the concentration camp, what shocked them most was the degradation they experienced there, the loss of their human dignity, and their expulsion from a bourgeois community of values to which they had felt they belonged. They were forced to realize that they had been handed over as helpless victims to the violence of SS thugs.

Imprisonment in the concentration camp after the November pogroms banished any remaining illusions that the men had about continuing to live in Nazi Germany.

Release

The large majority of the pogrom prisoners were released within a few months. The ill and men over 60 were the first to be discharged in mid-November 1938, followed by veterans of World War I and everyone under 16 years of age. In December, the SS released about 150-250 Jewish prisoners each day; by New Year 1939, 958 of the original 6,320 men were still in th camp.

The release process was also rife with harassment and caprice. The men’s clothing and valuables were returned to them, and they had to swear not to speak about their experiences in the camp. They had to sign this with their names; the men were no longer numbers. However, they were only released under the condition that they would emigrate.